PYRAMIDS

PYRAMIDS

Architecture, Power, and Mystery

Architecture, Power, and Mystery

Architecture, Power, and Mystery

I. Pyramid Architecture

I. Pyramid Architecture

I. Pyramid Architecture

From tomb evolution to perfected form, engineering logic meets symbolism.

II. Monuments and Power

II. Monuments and Power

II. Monuments and Power

How architecture materializes authority, commands labor, and communicates power eternally.

III.The Colonial Imagination

III.The Colonial Imagination

III.The Colonial Imagination

How empires reinterpreted pyramids to legitimize conquest, anxiety, identity formation.

IV. The Sublime and the Sacred

IV. The Sublime and the Sacred

IV. The Sublime and the Sacred

Why overwhelming scale triggers awe, terror, transcendence across cultures universally.

V.The Science of Permanence

V.The Science of Permanence

V.The Science of Permanence

Engineering decisions that enabled pyramids to endure millennia without maintenance.

Engineering decisions that enabled pyramids to endure millennia without maintenance.

VI. Sacred Geometry and Exactitude

VI. Sacred Geometry and Exactitude

VI. Sacred Geometry and Exactitude

How geometry, astronomy, and craft encoded divinity into precise architecture.

VII.The Mystery Industrial Complex

VII.The Mystery Industrial Complex

VII.The Mystery Industrial Complex

Why mystery, conspiracy, and spectacle thrive despite overwhelming archaeological evidence.

Why mystery, conspiracy, and spectacle thrive despite overwhelming archaeological evidence.

I. Pyramid Architecture

I. Pyramid Architecture

I. Pyramid Architecture

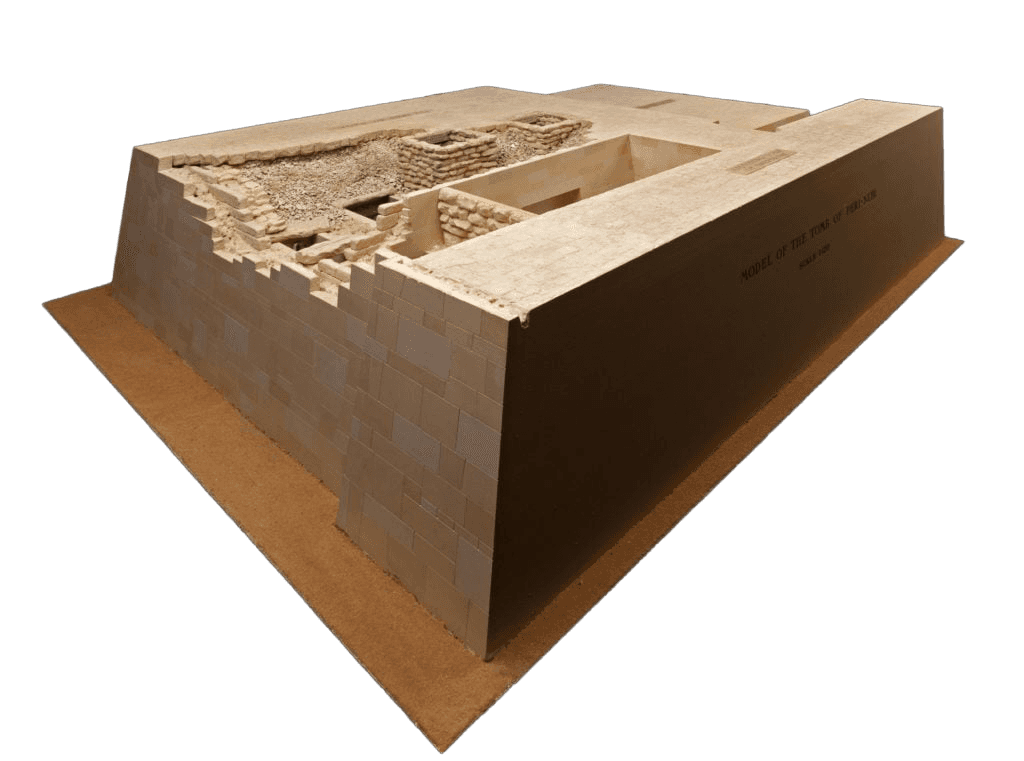

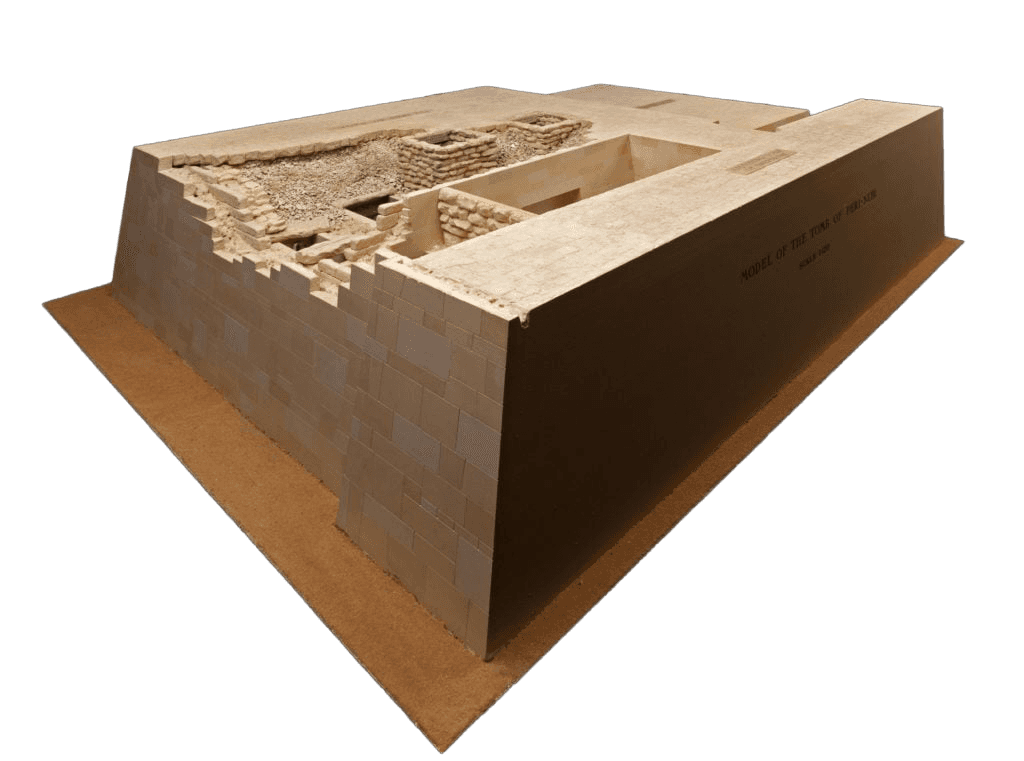

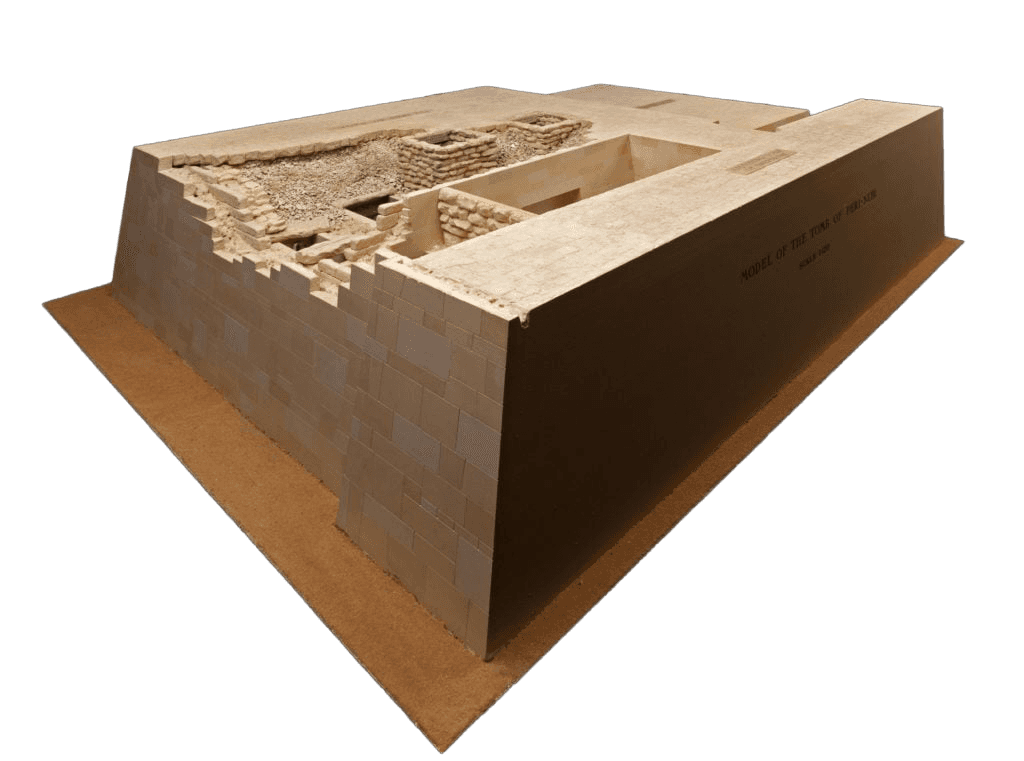

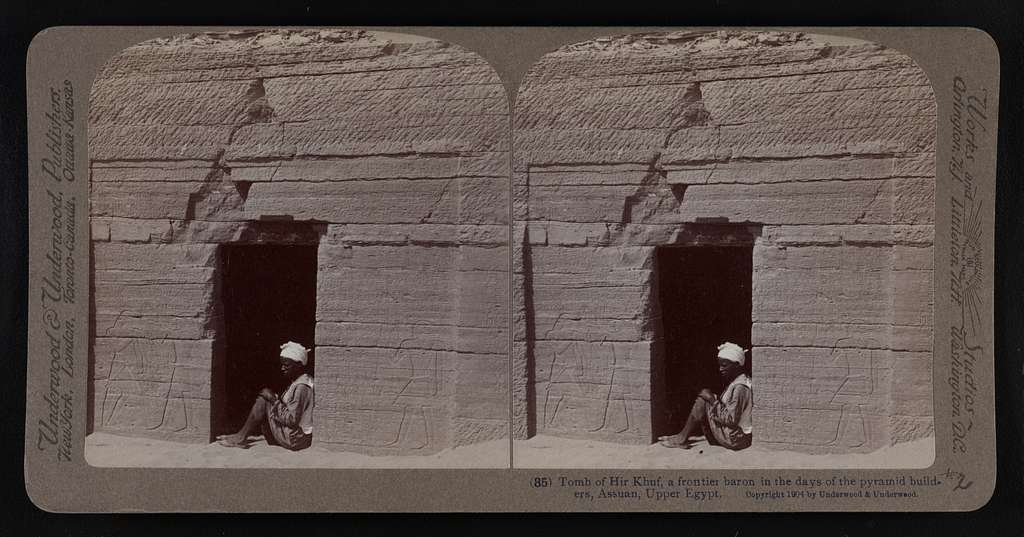

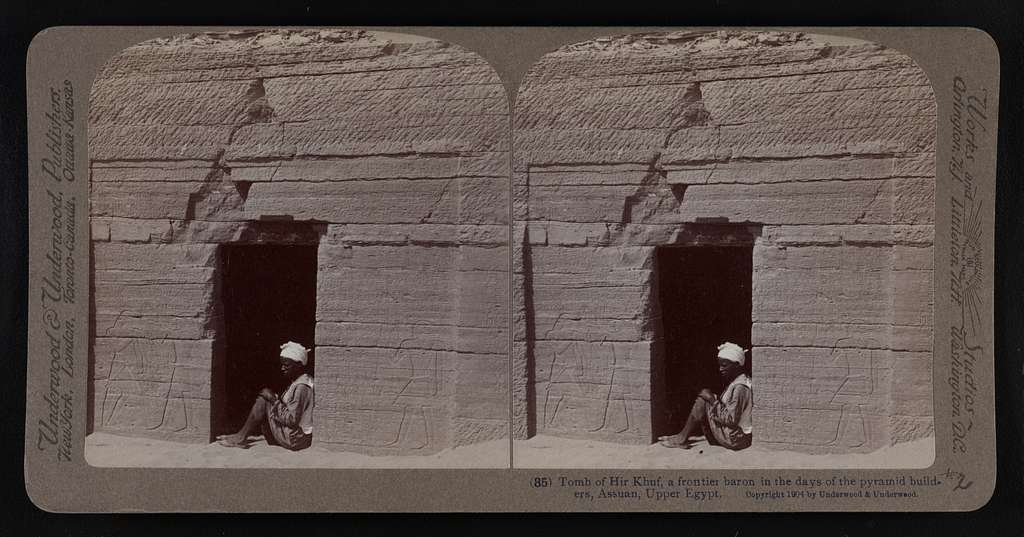

Late in Dynasty 5, the palace administrator Perneb built a tomb at Saqqara, twenty miles south of Giza. The tomb included an underground burial chamber and a limestone building called a mastaba. - Source

Late in Dynasty 5, the palace administrator Perneb built a tomb at Saqqara, twenty miles south of Giza. The tomb included an underground burial chamber and a limestone building called a mastaba. - Source

Late in Dynasty 5, the palace administrator Perneb built a tomb at Saqqara, twenty miles south of Giza. The tomb included an underground burial chamber and a limestone building called a mastaba. - Source

Early Egyptian rulers faced a fundamental architectural problem: how to create a tomb that would physically embody their divine status and ensure their eternal legacy? The traditional mastaba tombs, low rectangular structures made from mud brick, were adequate for nobles but insufficient for expressing pharaonic power. These structures were temporary, modest in scale, and vulnerable to the elements. So the question came up: how do you create a structure so monumental, so permanent, that it commands reverence for thousands of years?

The Solution: Around 2700 BCE, Egyptian architecture underwent a radical transformation that answered this challenge through a series of innovations in material and form.

Early Egyptian rulers faced a fundamental architectural problem: how to create a tomb that would physically embody their divine status and ensure their eternal legacy? The traditional mastaba tombs, low rectangular structures made from mud brick, were adequate for nobles but insufficient for expressing pharaonic power. These structures were temporary, modest in scale, and vulnerable to the elements. So the question came up: how do you create a structure so monumental, so permanent, that it commands reverence for thousands of years?

The Solution: Around 2700 BCE, Egyptian architecture underwent a radical transformation that answered this challenge through a series of innovations in material and form.

Early Egyptian rulers faced a fundamental architectural problem: how to create a tomb that would physically embody their divine status and ensure their eternal legacy? The traditional mastaba tombs, low rectangular structures made from mud brick, were adequate for nobles but insufficient for expressing pharaonic power. These structures were temporary, modest in scale, and vulnerable to the elements. So the question came up: how do you create a structure so monumental, so permanent, that it commands reverence for thousands of years?

The Solution: Around 2700 BCE, Egyptian architecture underwent a radical transformation that answered this challenge through a series of innovations in material and form.

The Pyramidal Shape

The independent development of pyramid forms across cultures suggests this shape solves universal architectural problems better than alternatives. Understanding why requires examining the geometric, structural, and symbolic advantages that make pyramids optimal solutions for monumental architecture.

Structural logic:

From an engineering perspective, the pyramid is perfect for massive construction. They have:

A wide base distributes weight efficiently

Minimal internal support needed

Resistance to earthquakes and erosion

As the structure rises, each level is smaller and lighter than the one below, creating a natural tapering that ensures the structure never bears more weight than its materials can support. The triangular profile resists lateral forces from wind and earthquakes. There's no large flat surface for wind to push against, and the low center of gravity prevents toppling. The pyramid is essentially a solid mass that makes structural failure nearly impossible.

The Pyramidal Shape

The independent development of pyramid forms across cultures suggests this shape solves universal architectural problems better than alternatives. Understanding why requires examining the geometric, structural, and symbolic advantages that make pyramids optimal solutions for monumental architecture.

Structural logic:

From an engineering perspective, the pyramid is perfect for massive construction. They have:

A wide base distributes weight efficiently

Minimal internal support needed

Resistance to earthquakes and erosion

As the structure rises, each level is smaller and lighter than the one below, creating a natural tapering that ensures the structure never bears more weight than its materials can support. The triangular profile resists lateral forces from wind and earthquakes. There's no large flat surface for wind to push against, and the low center of gravity prevents toppling. The pyramid is essentially a solid mass that makes structural failure nearly impossible.

The Pyramidal Shape

The independent development of pyramid forms across cultures suggests this shape solves universal architectural problems better than alternatives. Understanding why requires examining the geometric, structural, and symbolic advantages that make pyramids optimal solutions for monumental architecture.

Structural logic:

From an engineering perspective, the pyramid is perfect for massive construction. They have:

A wide base distributes weight efficiently

Minimal internal support needed

Resistance to earthquakes and erosion

As the structure rises, each level is smaller and lighter than the one below, creating a natural tapering that ensures the structure never bears more weight than its materials can support. The triangular profile resists lateral forces from wind and earthquakes. There's no large flat surface for wind to push against, and the low center of gravity prevents toppling. The pyramid is essentially a solid mass that makes structural failure nearly impossible.

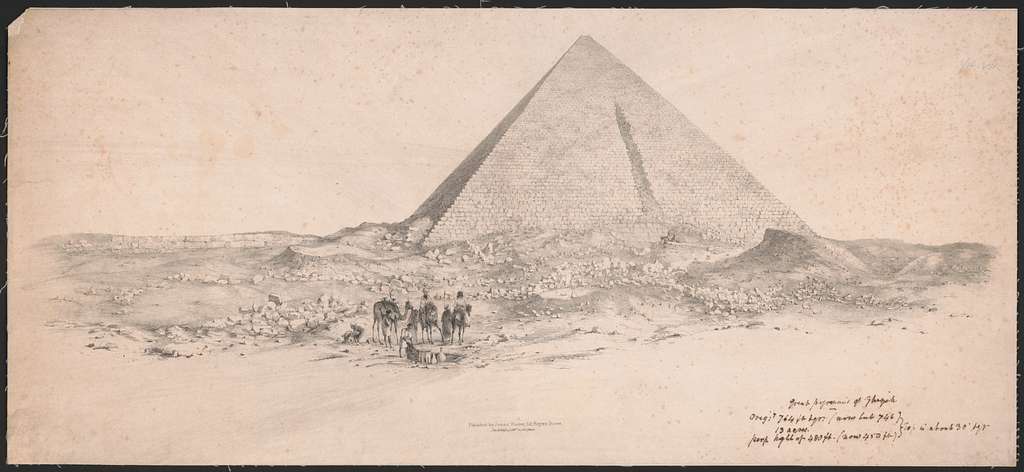

Wide photograph of the Giza pyramid complex dominating the surrounding desert, emphasizing monumental scale, geometric clarity, and landscape control that visually communicates political authority, cosmic order, and symbolic power.- Source

Wide photograph of the Giza pyramid complex dominating the surrounding desert, emphasizing monumental scale, geometric clarity, and landscape control that visually communicates political authority, cosmic order, and symbolic power.- Source

Wide photograph of the Giza pyramid complex dominating the surrounding desert, emphasizing monumental scale, geometric clarity, and landscape control that visually communicates political authority, cosmic order, and symbolic power.- Source

Symbolic power:

Symbolically, the pyramid's form communicates specific messages across cultures. The apex pointing skyward creates a visual connection between earth and sky, making the structure a physical manifestation of the axis mundi, the cosmic axis connecting different realms of existence. The simplicity is also remarkable; four triangles meeting at a point, suggesting fundamental truth and eternal principles rather than human artifice. The visibility from great distances ensures the structure dominates its landscape, continuously reminding viewers of the power behind its construction.

Construction practicality:

From a practical standpoint, pyramids are remarkably buildable despite their scale. They

Can be built without advanced mathematics

Each level provides platform for next level

Easy to survey and plan

Yet, they underwent a sequence of problem-solving iterations for perfection through centuries.

Symbolic power:

Symbolically, the pyramid's form communicates specific messages across cultures. The apex pointing skyward creates a visual connection between earth and sky, making the structure a physical manifestation of the axis mundi, the cosmic axis connecting different realms of existence. The simplicity is also remarkable; four triangles meeting at a point, suggesting fundamental truth and eternal principles rather than human artifice. The visibility from great distances ensures the structure dominates its landscape, continuously reminding viewers of the power behind its construction.

Construction practicality:

From a practical standpoint, pyramids are remarkably buildable despite their scale. They

Can be built without advanced mathematics

Each level provides platform for next level

Easy to survey and plan

Yet, they underwent a sequence of problem-solving iterations for perfection through centuries.

First Attempt: The Step Pyramid of Djoser

The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, designed by history's first named architect Imhotep, represented humanity's first massive stone structure which was six terraces stacked skyward, visible for miles. It's key architectural innovations were:

Transition from mud brick (mastabas) to limestone construction

Vertical monumentality: 62 meters high!

First structure designed to last beyond temporary use

This wasn't merely a larger tomb, it was a fundamental reimagining of what architecture could be. By transitioning from organic materials to stone, Imhotep created a new architectural language of permanence. The vertical stacking of terraces solved multiple problems simultaneously: it created unprecedented height for visibility, suggested a stairway to the heavens that aligned with Egyptian cosmology, and distributed the massive weight of stone in a structurally stable configuration.

First Attempt: The Step Pyramid of Djoser

The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, designed by history's first named architect Imhotep, represented humanity's first massive stone structure which was six terraces stacked skyward, visible for miles. It's key architectural innovations were:

Transition from mud brick (mastabas) to limestone construction

Vertical monumentality: 62 meters high!

First structure designed to last beyond temporary use

This wasn't merely a larger tomb, it was a fundamental reimagining of what architecture could be. By transitioning from organic materials to stone, Imhotep created a new architectural language of permanence. The vertical stacking of terraces solved multiple problems simultaneously: it created unprecedented height for visibility, suggested a stairway to the heavens that aligned with Egyptian cosmology, and distributed the massive weight of stone in a structurally stable configuration.

First Attempt: The Step Pyramid of Djoser

The Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, designed by history's first named architect Imhotep, represented humanity's first massive stone structure which was six terraces stacked skyward, visible for miles. It's key architectural innovations were:

Transition from mud brick (mastabas) to limestone construction

Vertical monumentality: 62 meters high!

First structure designed to last beyond temporary use

This wasn't merely a larger tomb, it was a fundamental reimagining of what architecture could be. By transitioning from organic materials to stone, Imhotep created a new architectural language of permanence. The vertical stacking of terraces solved multiple problems simultaneously: it created unprecedented height for visibility, suggested a stairway to the heavens that aligned with Egyptian cosmology, and distributed the massive weight of stone in a structurally stable configuration.

The Bent Pyramid represents a change from the step-sided pyramids of before to smooth-sided pyramids. It has been suggested that due to the steepness of the original angle of inclination the structure may have begun to show signs of instability during construction - Source

The Bent Pyramid represents a change from the step-sided pyramids of before to smooth-sided pyramids. It has been suggested that due to the steepness of the original angle of inclination the structure may have begun to show signs of instability during construction - Source

The Bent Pyramid represents a change from the step-sided pyramids of before to smooth-sided pyramids. It has been suggested that due to the steepness of the original angle of inclination the structure may have begun to show signs of instability during construction - Source

Once the principle of stone pyramid construction was established, Egyptian architects evolved from stepped pyramids to the aesthetically ideal form of smooth-sided true pyramids. The geometric perfection of unbroken triangular sides held both symbolic meaning (representing sun rays) and engineering challenges. The critical question was: what angle could support a smooth-sided pyramid at monumental scale without structural failure?

Pharaoh Sneferu's Bent Pyramid documents trial and error in real time. Builders started with a steep angle but realized midway the structure would collapse under its own weight. Rather than abandon the project, they adjusted by changing the slope and creating the distinctive "bent" silhouette.

Once the principle of stone pyramid construction was established, Egyptian architects evolved from stepped pyramids to the aesthetically ideal form of smooth-sided true pyramids. The geometric perfection of unbroken triangular sides held both symbolic meaning (representing sun rays) and engineering challenges. The critical question was: what angle could support a smooth-sided pyramid at monumental scale without structural failure?

Pharaoh Sneferu's Bent Pyramid documents trial and error in real time. Builders started with a steep angle but realized midway the structure would collapse under its own weight. Rather than abandon the project, they adjusted by changing the slope and creating the distinctive "bent" silhouette.

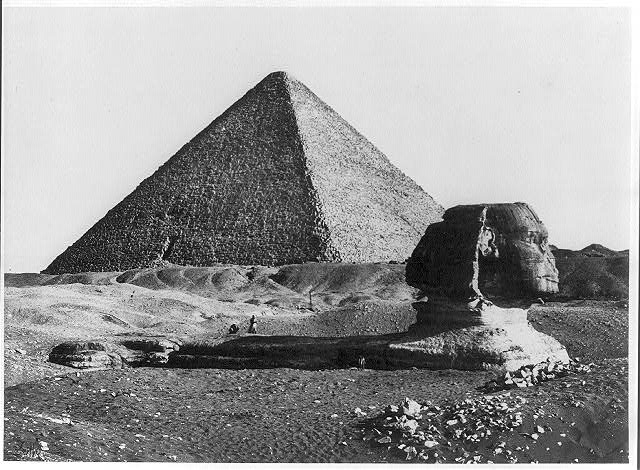

A reconstructed view of the Great Pyramid of Giza, shown with its original white limestone casing and a gilded capstone. Commissioned as a royal tomb for the Egyptian pharaoh Khufu, the pyramid was constructed between approximately 2584 and 2561 BCE and stands as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. - Source

A reconstructed view of the Great Pyramid of Giza, shown with its original white limestone casing and a gilded capstone. Commissioned as a royal tomb for the Egyptian pharaoh Khufu, the pyramid was constructed between approximately 2584 and 2561 BCE and stands as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. - Source

A reconstructed view of the Great Pyramid of Giza, shown with its original white limestone casing and a gilded capstone. Commissioned as a royal tomb for the Egyptian pharaoh Khufu, the pyramid was constructed between approximately 2584 and 2561 BCE and stands as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. - Source

Mastering the Form: The Red Pyramid

Having identified the structural problem with steep angles through the Bent Pyramid experience, Sneferu's architects needed to determine the optimal angle that could support a true pyramid from base to apex. This required calculating the relationship between height, base width, and slope to ensure structural integrity while maintaining impressive scale.

Sneferu's second attempt, the Red Pyramid, achieved smooth, unbroken sides from base to apex, the first true pyramid. The 43-degree angle became the standard for structural stability.

This seemingly simple achievement, maintaining a consistent angle throughout, represents a sophisticated understanding of load distribution, material properties, and geometric relationships. The 43-degree slope provided enough height for visual impact while ensuring each stone course could support the weight above it without exceeding the compression strength of limestone.

Mastering the Form: The Red Pyramid

Having identified the structural problem with steep angles through the Bent Pyramid experience, Sneferu's architects needed to determine the optimal angle that could support a true pyramid from base to apex. This required calculating the relationship between height, base width, and slope to ensure structural integrity while maintaining impressive scale.

Sneferu's second attempt, the Red Pyramid, achieved smooth, unbroken sides from base to apex, the first true pyramid. The 43-degree angle became the standard for structural stability.

This seemingly simple achievement, maintaining a consistent angle throughout, represents a sophisticated understanding of load distribution, material properties, and geometric relationships. The 43-degree slope provided enough height for visual impact while ensuring each stone course could support the weight above it without exceeding the compression strength of limestone.

Mastering the Form: The Red Pyramid

Having identified the structural problem with steep angles through the Bent Pyramid experience, Sneferu's architects needed to determine the optimal angle that could support a true pyramid from base to apex. This required calculating the relationship between height, base width, and slope to ensure structural integrity while maintaining impressive scale.

Sneferu's second attempt, the Red Pyramid, achieved smooth, unbroken sides from base to apex, the first true pyramid. The 43-degree angle became the standard for structural stability.

This seemingly simple achievement, maintaining a consistent angle throughout, represents a sophisticated understanding of load distribution, material properties, and geometric relationships. The 43-degree slope provided enough height for visual impact while ensuring each stone course could support the weight above it without exceeding the compression strength of limestone.

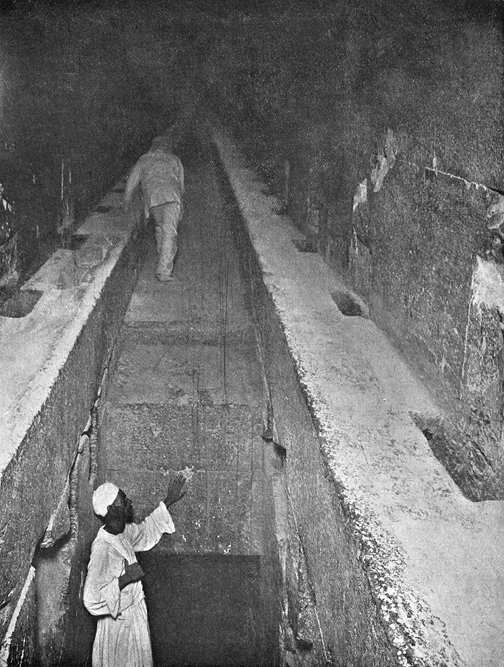

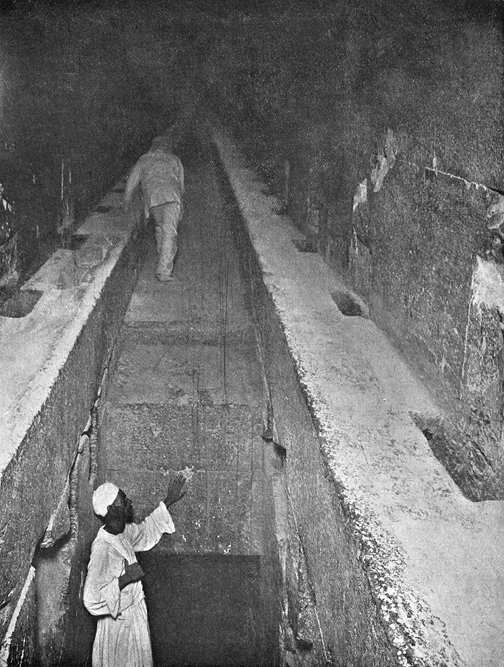

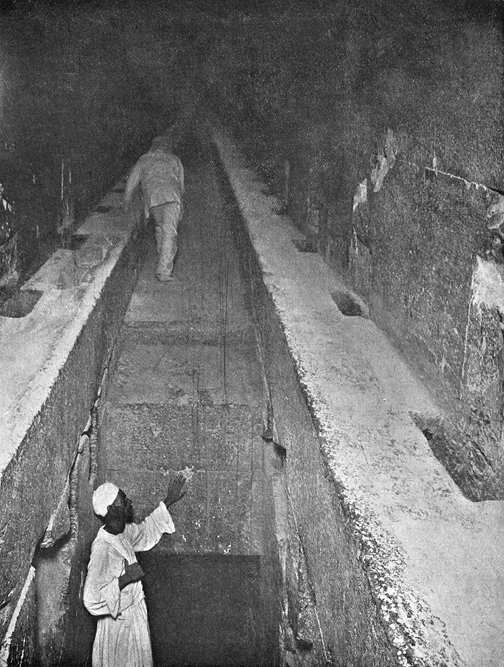

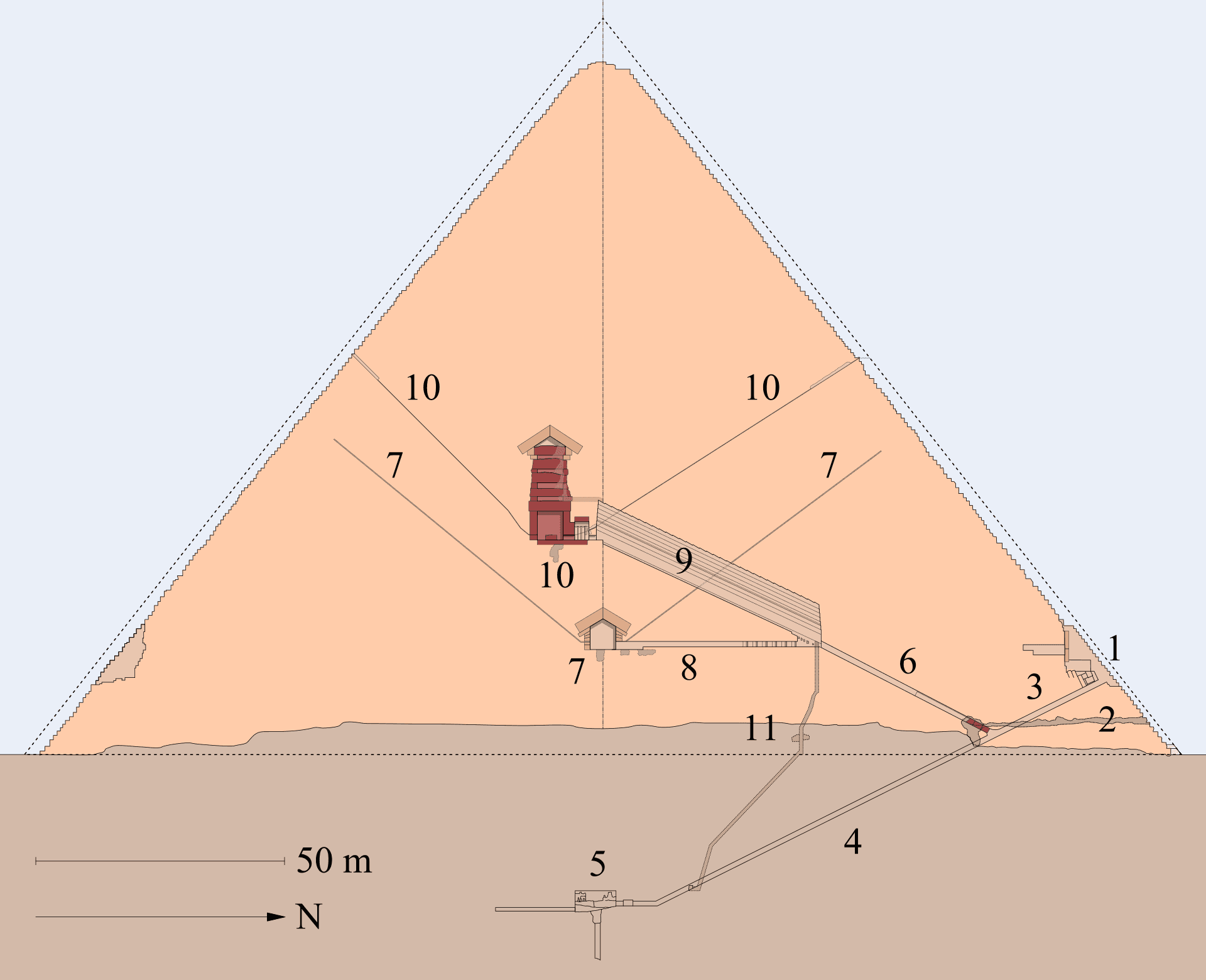

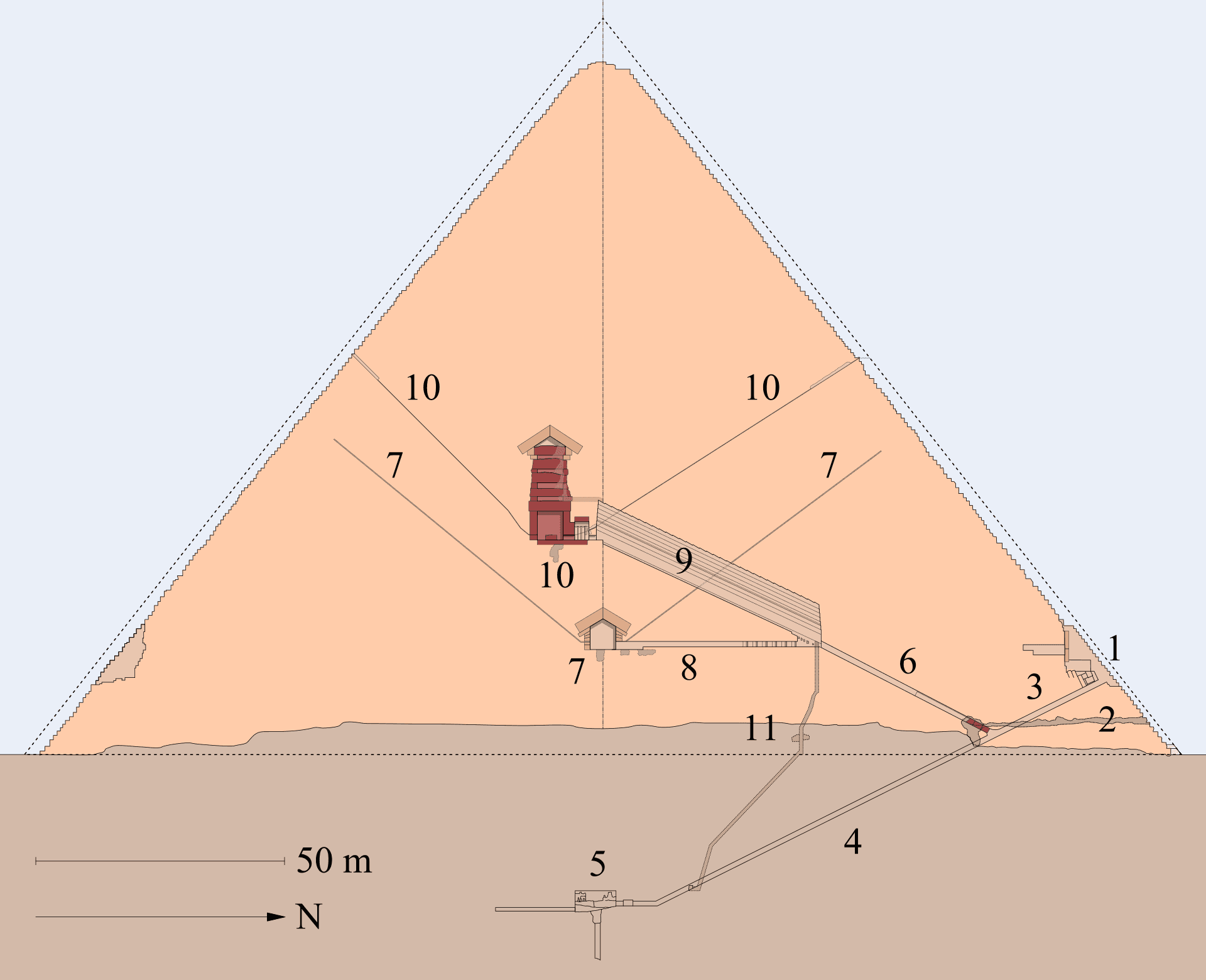

By the time Pharaoh Khufu commissioned his pyramid, Egyptian architects had accumulated decades of structural knowledge. However, Khufu's ambition created a new challenge: building at a scale that exceeded all previous attempts while achieving levels of precision that would demonstrate absolute mastery. The engineering problem was multifaceted: maintain geometric accuracy across millions of blocks, align a massive structure to celestial directions, level a foundation across acres of uneven bedrock, and do all of this while coordinating tens of thousands of workers over decades.

Khufu's Great Pyramid at Giza (c. 2580-2560 BCE) remained Earth's tallest structure for 4,000 years. Its precision rivals modern surveying equipment, but was achieved with Bronze Age tools. The alignment to true north required astronomical observation methods sophisticated enough to compete with magnetic compasses (which hadn't been invented). The level base required excavating bedrock and using water-leveling techniques across massive distances. The tight-fitting joints required custom-shaping each block to match its neighbors while maintaining overall structural integrity. This convergence of solutions, material science, surveying, logistics, quality control, represents ancient Egypt's peak architectural achievement.

By the time Pharaoh Khufu commissioned his pyramid, Egyptian architects had accumulated decades of structural knowledge. However, Khufu's ambition created a new challenge: building at a scale that exceeded all previous attempts while achieving levels of precision that would demonstrate absolute mastery. The engineering problem was multifaceted: maintain geometric accuracy across millions of blocks, align a massive structure to celestial directions, level a foundation across acres of uneven bedrock, and do all of this while coordinating tens of thousands of workers over decades.

Khufu's Great Pyramid at Giza (c. 2580-2560 BCE) remained Earth's tallest structure for 4,000 years. Its precision rivals modern surveying equipment, but was achieved with Bronze Age tools. The alignment to true north required astronomical observation methods sophisticated enough to compete with magnetic compasses (which hadn't been invented). The level base required excavating bedrock and using water-leveling techniques across massive distances. The tight-fitting joints required custom-shaping each block to match its neighbors while maintaining overall structural integrity. This convergence of solutions, material science, surveying, logistics, quality control, represents ancient Egypt's peak architectural achievement.

Architecture from Progression

The pharaohs succeeded in capturing the imagination of the future. We're still studying Pyramids, still stand in awe in their shadows, 4,500 years later. The progression from Djoser's Step Pyramid through the Bent Pyramid to the Great Pyramid reveals a methodology we now call iterative design: build, test, observe, refine, rebuild. Each structure represented an experiment at massive scale, with real-world feedback directly informing the next project. This approach created institutional knowledge that accumulated across generations, with each architect building on the lessons learned by predecessors.

Architecture from Progression

The pharaohs succeeded in capturing the imagination of the future. We're still studying Pyramids, still stand in awe in their shadows, 4,500 years later. The progression from Djoser's Step Pyramid through the Bent Pyramid to the Great Pyramid reveals a methodology we now call iterative design: build, test, observe, refine, rebuild. Each structure represented an experiment at massive scale, with real-world feedback directly informing the next project. This approach created institutional knowledge that accumulated across generations, with each architect building on the lessons learned by predecessors.

Architecture from Progression

The pharaohs succeeded in capturing the imagination of the future. We're still studying Pyramids, still stand in awe in their shadows, 4,500 years later. The progression from Djoser's Step Pyramid through the Bent Pyramid to the Great Pyramid reveals a methodology we now call iterative design: build, test, observe, refine, rebuild. Each structure represented an experiment at massive scale, with real-world feedback directly informing the next project. This approach created institutional knowledge that accumulated across generations, with each architect building on the lessons learned by predecessors.

“Perfection emerges through repetition. Each built work tests assumptions, informs the next, and advances knowledge through making.”

“Perfection emerges through repetition. Each built work tests assumptions, informs the next, and advances knowledge through making.”

II. Monuments and Power

II. Monuments and Power

The Language of Permanence

Throughout history, rulers have faced the political challenge of legitimizing their authority and ensuring their legacy beyond their lifetime. Words can be forgotten, laws can be changed, and memories fade within generations. Demonstrating power through military might, wealth distribution, and administrative control works only during a ruler's life and immediate aftermath. How, then, do you create a physical statement of power so overwhelming, so permanent, that it continues communicating authority millennia after your death?

The Solution: When a pharaoh mobilizes tens of thousands of workers to build a pyramid, he demonstrates his ability to command resources, organize labor, and bend nature to his will. The pyramid is a physical manifestation of political power. It is impossible to ignore, impossible to forget.

This approach to architecture as political communication solves multiple problems simultaneously. First, the sheer resource investment proves economic capacity; only a truly wealthy state can divert this much labor and material to non-productive uses. Second, the organizational complexity demonstrates administrative sophistication. Coordinating tens of thousands of workers across decades requires bureaucratic systems not individual administrators. Third, the permanent nature of stone ensures the message persists independent of living memory, continuously reinforcing the power of the pharaoh's lineage. Finally, the monumental scale creates a psychological impact that abstract declarations of power cannot match. Standing before a 140-meter structure triggers physiological responses that establish authority at a visceral, non-rational level.

The Language of Permanence

Throughout history, rulers have faced the political challenge of legitimizing their authority and ensuring their legacy beyond their lifetime. Words can be forgotten, laws can be changed, and memories fade within generations. Demonstrating power through military might, wealth distribution, and administrative control works only during a ruler's life and immediate aftermath. How, then, do you create a physical statement of power so overwhelming, so permanent, that it continues communicating authority millennia after your death?

The Solution: When a pharaoh mobilizes tens of thousands of workers to build a pyramid, he demonstrates his ability to command resources, organize labor, and bend nature to his will. The pyramid is a physical manifestation of political power. It is impossible to ignore, impossible to forget.

This approach to architecture as political communication solves multiple problems simultaneously. First, the sheer resource investment proves economic capacity; only a truly wealthy state can divert this much labor and material to non-productive uses. Second, the organizational complexity demonstrates administrative sophistication. Coordinating tens of thousands of workers across decades requires bureaucratic systems not individual administrators. Third, the permanent nature of stone ensures the message persists independent of living memory, continuously reinforcing the power of the pharaoh's lineage. Finally, the monumental scale creates a psychological impact that abstract declarations of power cannot match. Standing before a 140-meter structure triggers physiological responses that establish authority at a visceral, non-rational level.

Defensive Design

Throughout history, conquering powers have attempted to destroy monuments left by previous rulers, both to access valuable building materials and to eliminate symbols of competing authority. The architectural question becomes: can a structure be designed not just to stand for centuries, but to actively resist attempts at demolition?

The pyramids' engineering creates an unexpected defensive capability. They're easier to build than to destroy, as demonstrated by a Sultan's attempts to destroy a Pyramid.

Defensive Design

Throughout history, conquering powers have attempted to destroy monuments left by previous rulers, both to access valuable building materials and to eliminate symbols of competing authority. The architectural question becomes: can a structure be designed not just to stand for centuries, but to actively resist attempts at demolition?

The pyramids' engineering creates an unexpected defensive capability. They're easier to build than to destroy, as demonstrated by a Sultan's attempts to destroy a Pyramid.

Defensive Design

Throughout history, conquering powers have attempted to destroy monuments left by previous rulers, both to access valuable building materials and to eliminate symbols of competing authority. The architectural question becomes: can a structure be designed not just to stand for centuries, but to actively resist attempts at demolition?

The pyramids' engineering creates an unexpected defensive capability. They're easier to build than to destroy, as demonstrated by a Sultan's attempts to destroy a Pyramid.

Eight months work resulted in this vertical gash on the northern face of the Pyramid of Menkaure.

Eight months work resulted in this vertical gash on the northern face of the Pyramid of Menkaure.

The Ayyubid sultan decided to demolish the pyramids at Giza for building materials or to eliminate symbols of polytheism but ultimately abandoned the project. Each massive stone block, once dropped, sank deep into sand. Extracting them required teams of oxen, wooden levers, and backbreaking labor. The vertical gash on the Pyramid of Menkaure remains today, ironically memorializing his failure.

The pyramids solved the demolition problem through several design features. First, the massive weight of individual blocks creates a practical barrier—each stone requires enormous effort to move even once dislodged. Second, the interlocking structure means removing one block doesn't trigger cascade failure—the remaining structure maintains integrity, requiring individual attention to each stone. Third, the solid mass construction means there's no easy way to attack structural weak points. Unlike columned buildings where removing key supports causes collapse, pyramids distribute load so evenly that targeted demolition is ineffective. Finally, the desert location means dropped blocks immediately sink into sand, adding the additional labor of excavation to every stone removed. This combination of factors makes systematic demolition prohibitively expensive, even for powerful rulers with ideological motivations.

The pyramids weren't just well-built; they were weaponized architecture. They were designed to outlast and challenge future powers.

The Ayyubid sultan decided to demolish the pyramids at Giza for building materials or to eliminate symbols of polytheism but ultimately abandoned the project. Each massive stone block, once dropped, sank deep into sand. Extracting them required teams of oxen, wooden levers, and backbreaking labor. The vertical gash on the Pyramid of Menkaure remains today, ironically memorializing his failure.

The pyramids solved the demolition problem through several design features. First, the massive weight of individual blocks creates a practical barrier—each stone requires enormous effort to move even once dislodged. Second, the interlocking structure means removing one block doesn't trigger cascade failure—the remaining structure maintains integrity, requiring individual attention to each stone. Third, the solid mass construction means there's no easy way to attack structural weak points. Unlike columned buildings where removing key supports causes collapse, pyramids distribute load so evenly that targeted demolition is ineffective. Finally, the desert location means dropped blocks immediately sink into sand, adding the additional labor of excavation to every stone removed. This combination of factors makes systematic demolition prohibitively expensive, even for powerful rulers with ideological motivations.

The pyramids weren't just well-built; they were weaponized architecture. They were designed to outlast and challenge future powers.

Pyramids as Political Theater

The Construction Ritual

Beyond the completed structure, the construction process itself served crucial political functions. A pyramid project created continuous public spectacle over decades, ensuring every generation experienced direct evidence of pharaonic power. The challenge was transforming construction logistics into political communication.

Pyramids as Political Theater

The Construction Ritual

Beyond the completed structure, the construction process itself served crucial political functions. A pyramid project created continuous public spectacle over decades, ensuring every generation experienced direct evidence of pharaonic power. The challenge was transforming construction logistics into political communication.

Pyramids as Political Theater

The Construction Ritual

Beyond the completed structure, the construction process itself served crucial political functions. A pyramid project created continuous public spectacle over decades, ensuring every generation experienced direct evidence of pharaonic power. The challenge was transforming construction logistics into political communication.

Nation building:

Projects lasted decades, so every generation witnessed royal power

Scale demonstrated organizational capability over time

Worksites became pilgrimage destinations

The extended timeline solved a succession problem: A project spanning decades means multiple generations see it, creating continuity that transcends individual pharaohs' reigns. Citizens couldn't remember a time "before the pyramid," making royal power seem eternal rather than contingent.

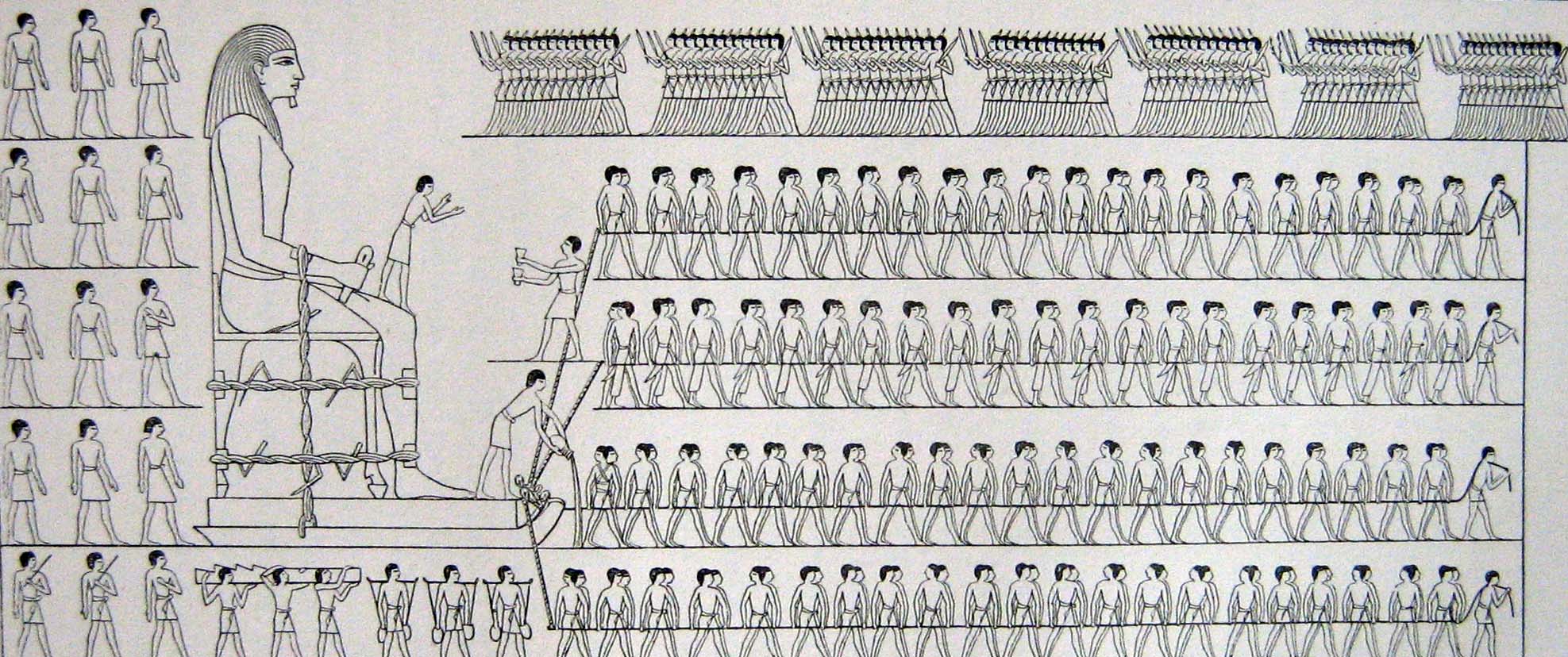

Deir el-Medina is the modern Arabic name for the worker's village. They housed the artisans and craftsmen who built the royal tombs in the nearby Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens. - Source

Deir el-Medina is the modern Arabic name for the worker's village. They housed the artisans and craftsmen who built the royal tombs in the nearby Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens. - Source

Employment:

Most workers were paid laborers, not slaves

Archaeological evidence shows workers' villages with medical care and nutrition

Pyramid projects provided employment during Nile flood season

The employment strategy solved multiple problems simultaneously. During Nile flood seasons when agricultural work was impossible, pyramid construction absorbed surplus labor that might otherwise create social instability. By paying workers rather than enslaving them, pharaohs created economic investment in the project's success, with workers' pride and economic dependence aligning their interests with completing the royal vision.

Employment:

Most workers were paid laborers, not slaves

Archaeological evidence shows workers' villages with medical care and nutrition

Pyramid projects provided employment during Nile flood season

The employment strategy solved multiple problems simultaneously. During Nile flood seasons when agricultural work was impossible, pyramid construction absorbed surplus labor that might otherwise create social instability. By paying workers rather than enslaving them, pharaohs created economic investment in the project's success, with workers' pride and economic dependence aligning their interests with completing the royal vision.

Employment:

Most workers were paid laborers, not slaves

Archaeological evidence shows workers' villages with medical care and nutrition

Pyramid projects provided employment during Nile flood season

The employment strategy solved multiple problems simultaneously. During Nile flood seasons when agricultural work was impossible, pyramid construction absorbed surplus labor that might otherwise create social instability. By paying workers rather than enslaving them, pharaohs created economic investment in the project's success, with workers' pride and economic dependence aligning their interests with completing the royal vision.

Religious legitimacy:

Connected pharaoh to gods

Demonstrated divine favor

Pyramid as sacred architecture reinforced theocratic power

By framing pyramid construction as religious obligation rather than merely personal aggrandizement, pharaohs positioned themselves as essential intermediaries between human and divine realms. The successful completion of such massive projects "proved" divine favor.

Religious legitimacy:

Connected pharaoh to gods

Demonstrated divine favor

Pyramid as sacred architecture reinforced theocratic power

By framing pyramid construction as religious obligation rather than merely personal aggrandizement, pharaohs positioned themselves as essential intermediaries between human and divine realms. The successful completion of such massive projects "proved" divine favor.

Religious legitimacy:

Connected pharaoh to gods

Demonstrated divine favor

Pyramid as sacred architecture reinforced theocratic power

By framing pyramid construction as religious obligation rather than merely personal aggrandizement, pharaohs positioned themselves as essential intermediaries between human and divine realms. The successful completion of such massive projects "proved" divine favor.

The Psychology of Scale

The Perceptual Challenge: Architects deliberately manipulated human perception to achieve political and religious goals. What specific architectural strategies trigger the psychological responses that establish authority?

Embodied experience:

When confronting truly massive structures, the human body provides immediate feedback that establishes the building's dominance.

Human scale disappears confronting 140-meter structures

Physical discomfort creates psychological impact

Body's smallness becomes impossible to ignore

The Psychology of Scale

The Perceptual Challenge: Architects deliberately manipulated human perception to achieve political and religious goals. What specific architectural strategies trigger the psychological responses that establish authority?

Embodied experience:

When confronting truly massive structures, the human body provides immediate feedback that establishes the building's dominance.

Human scale disappears confronting 140-meter structures

Physical discomfort creates psychological impact

Body's smallness becomes impossible to ignore

The Psychology of Scale

The Perceptual Challenge: Architects deliberately manipulated human perception to achieve political and religious goals. What specific architectural strategies trigger the psychological responses that establish authority?

Embodied experience:

When confronting truly massive structures, the human body provides immediate feedback that establishes the building's dominance.

Human scale disappears confronting 140-meter structures

Physical discomfort creates psychological impact

Body's smallness becomes impossible to ignore

Peripheral vision cannot capture the entire structure simultaneously, forcing the viewer to move or turn. The building dictates your physical behavior. These responses operates below conscious reasoning, making it powerful propaganda that doesn't require literacy or cultural knowledge to comprehend.

Spatial domination:

The spatial impact solves the problem of maintaining presence across distance. Unlike human authorities who can only be in one place at a time, monumental architecture remains visible across vast areas, creating omnipresent reminders of power.

Visible from miles away (inescapable presence) and reorganizes landscape

Controls sight lines and movement through space

The enormity of the Pyramids reorganizes the landscape itself, becoming the reference point by which everything else is oriented "north of the pyramid," "three days' walk from the great temple." This controls not just physical navigation but mental maps, ensuring the monument occupies central position in how people conceptualize their world.

Peripheral vision cannot capture the entire structure simultaneously, forcing the viewer to move or turn. The building dictates your physical behavior. These responses operates below conscious reasoning, making it powerful propaganda that doesn't require literacy or cultural knowledge to comprehend.

Spatial domination:

The spatial impact solves the problem of maintaining presence across distance. Unlike human authorities who can only be in one place at a time, monumental architecture remains visible across vast areas, creating omnipresent reminders of power.

Visible from miles away (inescapable presence) and reorganizes landscape

Controls sight lines and movement through space

The enormity of the Pyramids reorganizes the landscape itself, becoming the reference point by which everything else is oriented "north of the pyramid," "three days' walk from the great temple." This controls not just physical navigation but mental maps, ensuring the monument occupies central position in how people conceptualize their world.

Peripheral vision cannot capture the entire structure simultaneously, forcing the viewer to move or turn. The building dictates your physical behavior. These responses operates below conscious reasoning, making it powerful propaganda that doesn't require literacy or cultural knowledge to comprehend.

Spatial domination:

The spatial impact solves the problem of maintaining presence across distance. Unlike human authorities who can only be in one place at a time, monumental architecture remains visible across vast areas, creating omnipresent reminders of power.

Visible from miles away (inescapable presence) and reorganizes landscape

Controls sight lines and movement through space

The enormity of the Pyramids reorganizes the landscape itself, becoming the reference point by which everything else is oriented "north of the pyramid," "three days' walk from the great temple." This controls not just physical navigation but mental maps, ensuring the monument occupies central position in how people conceptualize their world.

The Irony of Transcendent Success

Pyramids no longer communicate Egyptian royal power. They've become symbols of human capability itself.

The pharaohs wanted to be remembered as gods. Instead, they proved humans can act like gods. Creating works that outlast empires and force people millennia later to wonder: "How?"

Meanings are not fixed in stone even when the stone endures. The pyramids now serve purposes their builders never imagined. The structures' success at permanence has made them available for continuous reinterpretation, demonstrating that while you can control what you build, you cannot control what it means to future generations whose contexts and concerns differ entirely from your own.

“Architecture is a political instrument: by engineering permanence, monuments signal authority, power, divine order, and cultural memory that edure long after rivals, dissent, and even the builders themselves had vanished.”

“Architecture is a political instrument: by engineering permanence, monuments signal authority, power, divine order, and cultural memory that edure long after rivals, dissent, and even the builders themselves had vanished.”

III. THE COLONIAL IMAGINATION

III. THE COLONIAL IMAGINATION

III. THE COLONIAL IMAGINATION

Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign (1798)

European powers in the age of colonialism needed to legitimize territorial conquest and cultural appropriation through intellectual frameworks. Military force could seize land, but claiming cultural and intellectual superiority required demonstrating that colonizers could understand and interpret colonized civilizations better than the people living there. The architectural dimension of this problem involved transforming physical monuments into data that could be extracted, transported, and reinterpreted in European contexts.

Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign (1798)

European powers in the age of colonialism needed to legitimize territorial conquest and cultural appropriation through intellectual frameworks. Military force could seize land, but claiming cultural and intellectual superiority required demonstrating that colonizers could understand and interpret colonized civilizations better than the people living there. The architectural dimension of this problem involved transforming physical monuments into data that could be extracted, transported, and reinterpreted in European contexts.

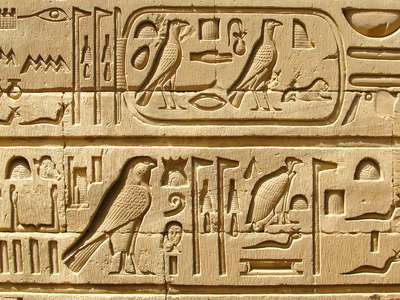

The Dual Invasion: Napoleon invaded Egypt with 50,000 soldiers and 167 scholars. The military campaign failed, but the scholarly mission succeeded spectacularly. Scientists and artists documented everything, eventually publishing Description de l'Égypte (1809-1829). 24 volumes introducing ancient Egypt to European imagination.

The scholars' documentation transformed Egyptian monuments into European intellectual property. The physical structures remained in Egypt, but the authoritative knowledge about them resided in European books, museums, and universities. Detailed architectural drawings allowed European architects to incorporate Egyptian motifs into Western buildings without consulting Egyptian sources. The Rosetta Stone's seizure and transport to London physically embodied this knowledge extraction, with the key to understanding Egyptian language now controlled by British institutions. The 24 volumes of Description de l'Égypte created a definitive European interpretation of Egypt that positioned French scholarship as more authoritative than contemporary Egyptian understanding, despite Egyptians living among and maintaining relationships with these monuments for millennia.

The Dual Invasion: Napoleon invaded Egypt with 50,000 soldiers and 167 scholars. The military campaign failed, but the scholarly mission succeeded spectacularly. Scientists and artists documented everything, eventually publishing Description de l'Égypte (1809-1829). 24 volumes introducing ancient Egypt to European imagination.

The scholars' documentation transformed Egyptian monuments into European intellectual property. The physical structures remained in Egypt, but the authoritative knowledge about them resided in European books, museums, and universities. Detailed architectural drawings allowed European architects to incorporate Egyptian motifs into Western buildings without consulting Egyptian sources. The Rosetta Stone's seizure and transport to London physically embodied this knowledge extraction, with the key to understanding Egyptian language now controlled by British institutions. The 24 volumes of Description de l'Égypte created a definitive European interpretation of Egypt that positioned French scholarship as more authoritative than contemporary Egyptian understanding, despite Egyptians living among and maintaining relationships with these monuments for millennia.

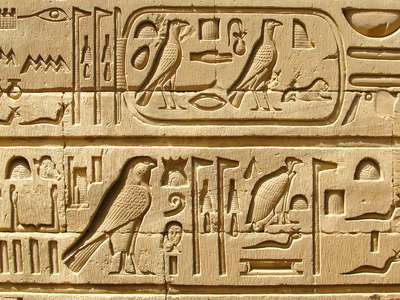

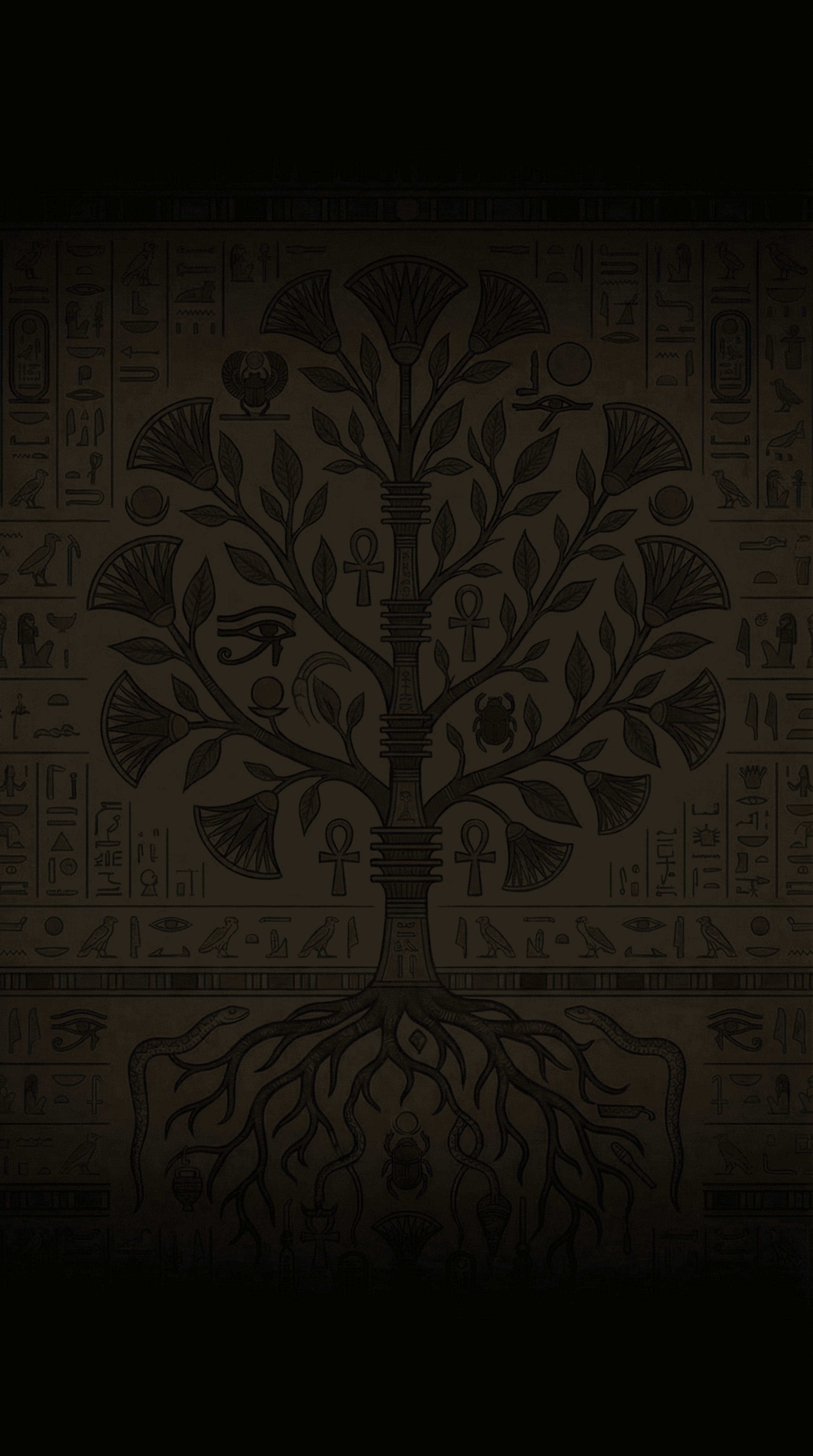

Carved hieroglyphs lining the stone walls of the Temple of Kom Ombo, Egypt, illustrating religious texts and ritual imagery preserved from the Ptolemaic period. - Source

Carved hieroglyphs lining the stone walls of the Temple of Kom Ombo, Egypt, illustrating religious texts and ritual imagery preserved from the Ptolemaic period. - Source

Carved hieroglyphs lining the stone walls of the Temple of Kom Ombo, Egypt, illustrating religious texts and ritual imagery preserved from the Ptolemaic period. - Source

While poetry and prose could articulate anxieties about imperial decline, visual arts faced the challenge of depicting this civilizational collapse in ways that resonated emotionally with Victorian audiences. How do you paint empire's fall in a manner that connects ancient Egyptian collapse to contemporary British concerns?

The Apocalyptic Vision: British painter John Martin's "The Seventh Plague of Egypt" (1823) shows Egypt consumed by biblical plague, fire and hail from blood-red sky while pyramids stand in background. Human figures flee in terror. The architecture, so permanent and proud, offers no protection against divine judgment.

While poetry and prose could articulate anxieties about imperial decline, visual arts faced the challenge of depicting this civilizational collapse in ways that resonated emotionally with Victorian audiences. How do you paint empire's fall in a manner that connects ancient Egyptian collapse to contemporary British concerns?

The Apocalyptic Vision: British painter John Martin's "The Seventh Plague of Egypt" (1823) shows Egypt consumed by biblical plague, fire and hail from blood-red sky while pyramids stand in background. Human figures flee in terror. The architecture, so permanent and proud, offers no protection against divine judgment.

British artist John Martin depicts the biblical plague of Ancient Egypt. Moses is calling down the violent storm of thunder while the Pyramids tower in the backdrop.

British artist John Martin depicts the biblical plague of Ancient Egypt. Moses is calling down the violent storm of thunder while the Pyramids tower in the backdrop.

British artist John Martin depicts the biblical plague of Ancient Egypt. Moses is calling down the violent storm of thunder while the Pyramids tower in the backdrop. - Source

The Sublime aesthetic:

Evokes terror, awe, and sense of the infinite

Humans appear insignificant against vast forces

Beauty mixed with fear

Martin's work solved the visualization problem through the aesthetic category of the Sublime, depicting scenes that inspire simultaneous attraction and terror, beauty and fear. By placing pyramids in apocalyptic biblical scenes, he connected ancient Egyptian monuments to a narrative familiar to Christian Victorian audiences while suggesting that even the most impressive human achievements offer no protection against divine or natural forces. The tiny human figures fleeing in his paintings established scale relationships that made viewers identify with the helpless victims rather than the powerful builders, transforming pyramids from symbols of human achievement into evidence of human limitations. This articulated Victorian anxieties perfectly. No matter how powerful British civilization became, forces beyond human control could destroy it as completely as ancient Egypt fell.

Martin's work articulated Victorian anxieties through Egyptian imagery: all power, no matter how great, is temporary.

The Sublime aesthetic:

Evokes terror, awe, and sense of the infinite

Humans appear insignificant against vast forces

Beauty mixed with fear

Martin's work solved the visualization problem through the aesthetic category of the Sublime, depicting scenes that inspire simultaneous attraction and terror, beauty and fear. By placing pyramids in apocalyptic biblical scenes, he connected ancient Egyptian monuments to a narrative familiar to Christian Victorian audiences while suggesting that even the most impressive human achievements offer no protection against divine or natural forces. The tiny human figures fleeing in his paintings established scale relationships that made viewers identify with the helpless victims rather than the powerful builders, transforming pyramids from symbols of human achievement into evidence of human limitations. This articulated Victorian anxieties perfectly. No matter how powerful British civilization became, forces beyond human control could destroy it as completely as ancient Egypt fell.

Martin's work articulated Victorian anxieties through Egyptian imagery: all power, no matter how great, is temporary.

The United States, as a young nation, faced a unique National Identity Challenge. How to create national symbols suggesting historical depth and legitimate authority when the country lacked ancient history? European nations could reference medieval castles and Roman ruins, but America's short history provided no comparable architectural heritage. The solution involved appropriating ancient symbols and reinterpreting them for republican purposes.

The U.S. adopted pyramid symbolism on currency. The one-dollar bill displays an unfinished pyramid with an eye hovering above, the Great Seal. America used this symbol to position itself as heir to Egypt's power and longevity. Its inclusion is often seen as a nod to the enduring nature of the United States, paralleling the enduring legacy of the Egyptian civilization.

The irony is that this adoption by a democracy inverted what pyramids actually symbolized: autocratic power, divine kingship, rigid hierarchy.

The United States, as a young nation, faced a unique National Identity Challenge. How to create national symbols suggesting historical depth and legitimate authority when the country lacked ancient history? European nations could reference medieval castles and Roman ruins, but America's short history provided no comparable architectural heritage. The solution involved appropriating ancient symbols and reinterpreting them for republican purposes.

The U.S. adopted pyramid symbolism on currency. The one-dollar bill displays an unfinished pyramid with an eye hovering above, the Great Seal. America used this symbol to position itself as heir to Egypt's power and longevity. Its inclusion is often seen as a nod to the enduring nature of the United States, paralleling the enduring legacy of the Egyptian civilization.

The irony is that this adoption by a democracy inverted what pyramids actually symbolized: autocratic power, divine kingship, rigid hierarchy.

The unfinished pyramid on the U.S. one-dollar note, drawn from the reverse of the Great Seal of the United States, symbolizes endurance, rational order, and the project of nation-building as an ongoing construction. Its truncated form suggests a structure still in progress - Source

The unfinished pyramid on the U.S. one-dollar note, drawn from the reverse of the Great Seal of the United States, symbolizes endurance, rational order, and the project of nation-building as an ongoing construction. Its truncated form suggests a structure still in progress - Source

The unfinished pyramid on the U.S. one-dollar note, drawn from the reverse of the Great Seal of the United States, symbolizes endurance, rational order, and the project of nation-building as an ongoing construction. Its truncated form suggests a structure still in progress - Source

This appropriation solved America's legitimacy problem through symbolic transfer. By placing a pyramid on its currency America claimed connection to ancient civilization's power while the unfinished top suggested ongoing progress and perfectibility. The hovering eye represented divine providence watching over the nation, replacing pharaonic divine kingship with more abstract supernatural oversight compatible with Christian democracy. The message to citizens and foreign observers was clear: despite being a young nation, America embodied principles as ancient and enduring as the pyramids.

This appropriation solved America's legitimacy problem through symbolic transfer. By placing a pyramid on its currency America claimed connection to ancient civilization's power while the unfinished top suggested ongoing progress and perfectibility. The hovering eye represented divine providence watching over the nation, replacing pharaonic divine kingship with more abstract supernatural oversight compatible with Christian democracy. The message to citizens and foreign observers was clear: despite being a young nation, America embodied principles as ancient and enduring as the pyramids.

“The same monument can represent divine power, imperial warning, or cultural heritage depending on who's telling the story. It's an enduring architectural symbol because it invites interpretation.”

“The same monument can represent divine power, imperial warning, or cultural heritage depending on who's telling the story. It's an enduring architectural symbol because it invites interpretation.”

Architectural symbols can be completely re-contextualized over time. Egyptian pyramids represented hierarchical society with god-king pharaohs at the apex and masses of subjects at the base, the antithesis of democratic ideals. American reinterpretation stripped away this context, treating the pyramid as a neutral symbol of strength and endurance that could represent any political system.

This demonstrates that architectural meaning is not intrinsic but constructed through interpretation, with symbolic forms becoming available for appropriation once separated from their original cultural contexts.

Architectural symbols can be completely re-contextualized over time. Egyptian pyramids represented hierarchical society with god-king pharaohs at the apex and masses of subjects at the base, the antithesis of democratic ideals. American reinterpretation stripped away this context, treating the pyramid as a neutral symbol of strength and endurance that could represent any political system.

This demonstrates that architectural meaning is not intrinsic but constructed through interpretation, with symbolic forms becoming available for appropriation once separated from their original cultural contexts.

IV. THE SUBLIME AND THE SACRED

IV. THE SUBLIME AND THE SACRED

IV. THE SUBLIME AND THE SACRED

Ordinary buildings can be understood through familiar perceptual frameworks: we gauge size relative to our bodies, assess functionality through mental categories, and evaluate aesthetics through learned preferences. But truly transformative architecture needs to overwhelm these normal perceptual processes, creating experiences that feel extraordinary. The question becomes: what specific architectural strategies reliably trigger responses of awe, wonder, and transcendence?

Ordinary buildings can be understood through familiar perceptual frameworks: we gauge size relative to our bodies, assess functionality through mental categories, and evaluate aesthetics through learned preferences. But truly transformative architecture needs to overwhelm these normal perceptual processes, creating experiences that feel extraordinary. The question becomes: what specific architectural strategies reliably trigger responses of awe, wonder, and transcendence?

The Physiological Impact of Scale

Standing at the Great Pyramid's base creates a specific feeling: breath held, thoughts quiet, confronted by something making you feel simultaneously insignificant and connected to things larger than yourself. Philosophers call this "the Sublime."

What is the Sublime?

Eighteenth-century philosophers sought to explain why certain encounters such as vast landscapes, violent storms, or monumental architecture produced responses fundamentally different from ordinary aesthetic pleasure. These experiences were not simply beautiful. They overwhelmed, unsettled, and compelled attention. Edmund Burke, writing in 1757, defined the Sublime as an affective state combining astonishment, terror, awe, and admiration. Unlike beauty, which invites calm and pleasurable contemplation, the Sublime exerts a kind of force over the viewer. It produces what Burke described as a pleasurable terror, an experience that destabilizes the senses and resists comfort, yet remains irresistible. In Burke’s framework, the defining feature of the Sublime is this tension. Attraction arises precisely from discomfort. Massive architecture, dangerous natural phenomena, and overwhelming artworks become desirable not despite their threat to perceptual ease, but because they push the viewer to the edge of sensory and emotional tolerance.

The Physiological Impact of Scale

Standing at the Great Pyramid's base creates a specific feeling: breath held, thoughts quiet, confronted by something making you feel simultaneously insignificant and connected to things larger than yourself. Philosophers call this "the Sublime."

What is the Sublime?

Eighteenth-century philosophers sought to explain why certain encounters such as vast landscapes, violent storms, or monumental architecture produced responses fundamentally different from ordinary aesthetic pleasure. These experiences were not simply beautiful. They overwhelmed, unsettled, and compelled attention. Edmund Burke, writing in 1757, defined the Sublime as an affective state combining astonishment, terror, awe, and admiration. Unlike beauty, which invites calm and pleasurable contemplation, the Sublime exerts a kind of force over the viewer. It produces what Burke described as a pleasurable terror, an experience that destabilizes the senses and resists comfort, yet remains irresistible. In Burke’s framework, the defining feature of the Sublime is this tension. Attraction arises precisely from discomfort. Massive architecture, dangerous natural phenomena, and overwhelming artworks become desirable not despite their threat to perceptual ease, but because they push the viewer to the edge of sensory and emotional tolerance.

The Physiological Impact of Scale

Standing at the Great Pyramid's base creates a specific feeling: breath held, thoughts quiet, confronted by something making you feel simultaneously insignificant and connected to things larger than yourself. Philosophers call this "the Sublime."

What is the Sublime?

Eighteenth-century philosophers sought to explain why certain encounters such as vast landscapes, violent storms, or monumental architecture produced responses fundamentally different from ordinary aesthetic pleasure. These experiences were not simply beautiful. They overwhelmed, unsettled, and compelled attention. Edmund Burke, writing in 1757, defined the Sublime as an affective state combining astonishment, terror, awe, and admiration. Unlike beauty, which invites calm and pleasurable contemplation, the Sublime exerts a kind of force over the viewer. It produces what Burke described as a pleasurable terror, an experience that destabilizes the senses and resists comfort, yet remains irresistible. In Burke’s framework, the defining feature of the Sublime is this tension. Attraction arises precisely from discomfort. Massive architecture, dangerous natural phenomena, and overwhelming artworks become desirable not despite their threat to perceptual ease, but because they push the viewer to the edge of sensory and emotional tolerance.

Ship in a storm by J.M. Turner embodies the Romantic sublime: human presence is reduced to fragility as swirling wind, sea, and snow overwhelm the composition, confronting the viewer with nature’s vast, uncontrollable power and the limits of human mastery.

Ship in a storm by J.M. Turner embodies the Romantic sublime: human presence is reduced to fragility as swirling wind, sea, and snow overwhelm the composition, confronting the viewer with nature’s vast, uncontrollable power and the limits of human mastery.

Ship in a storm by J.M. Turner embodies the Romantic sublime: human presence is reduced to fragility as swirling wind, sea, and snow overwhelm the composition, confronting the viewer with nature’s vast, uncontrollable power and the limits of human mastery. - Source

Immanuel Kant, writing in 1790, shifted the discussion from emotional response to cognitive structure. For Kant, the Sublime emerges when the mind confronts something so large or powerful that sensory perception fails altogether. In this moment of failure, reason intervenes. Although we cannot grasp the object fully through sight or sensation, we can comprehend it conceptually as magnitude, infinity, or totality. This transition from sensory inadequacy to rational comprehension produces the Sublime. The experience is humbling because it reveals the limits of the senses, but it is also empowering because it exposes a faculty of thought that exceeds those limits. When we encounter a structure too vast to take in at once, we discover not just the object’s scale, but our own capacity to think beyond immediate perception. In Kant’s account, the Sublime is therefore not located in the object itself, but in the mind’s realization of its own transcendent abilities.

Immanuel Kant, writing in 1790, shifted the discussion from emotional response to cognitive structure. For Kant, the Sublime emerges when the mind confronts something so large or powerful that sensory perception fails altogether. In this moment of failure, reason intervenes. Although we cannot grasp the object fully through sight or sensation, we can comprehend it conceptually as magnitude, infinity, or totality. This transition from sensory inadequacy to rational comprehension produces the Sublime. The experience is humbling because it reveals the limits of the senses, but it is also empowering because it exposes a faculty of thought that exceeds those limits. When we encounter a structure too vast to take in at once, we discover not just the object’s scale, but our own capacity to think beyond immediate perception. In Kant’s account, the Sublime is therefore not located in the object itself, but in the mind’s realization of its own transcendent abilities.

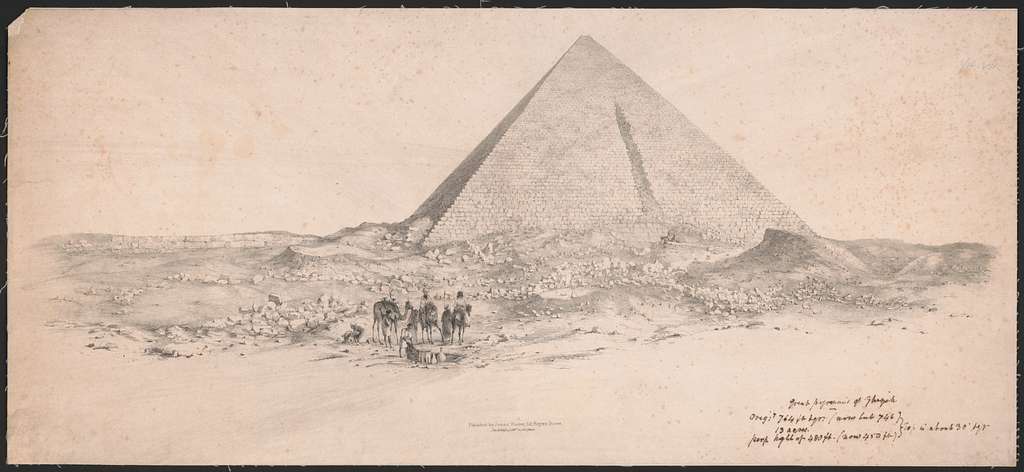

Seventeenth-century engraving depicting the Great Pyramid of Giza, illustrating European archaeological curiosity and travel narratives. Source

Seventeenth-century engraving depicting the Great Pyramid of Giza, illustrating European archaeological curiosity and travel narratives. Source

Seventeenth-century engraving depicting the Great Pyramid of Giza, illustrating European archaeological curiosity and travel narratives. Source

Pyramids as Sublime Objects

Understanding the Sublime as a psychological phenomenon allows us to analyze how pyramids deliberately engineer responses through specific architectural choices. The challenge for pyramid architects was creating forms that reliably trigger Sublime experiences across different viewers and cultural contexts. The solution involved maximizing multiple factors that converge to overwhelm normal perception.

Scale:

Too large to see all at once

Mass that seems impossible (2.3 million blocks)

Height dominating human construction for 4,000 years

Human vision has a finite field of view. Standing at the pyramid's base, you physically cannot see the entire structure without moving. This forces the viewer to mentally reconstruct the whole from partial views, engaging imagination rather than direct perception.

Pyramids as Sublime Objects

Understanding the Sublime as a psychological phenomenon allows us to analyze how pyramids deliberately engineer responses through specific architectural choices. The challenge for pyramid architects was creating forms that reliably trigger Sublime experiences across different viewers and cultural contexts. The solution involved maximizing multiple factors that converge to overwhelm normal perception.

Scale:

Too large to see all at once

Mass that seems impossible (2.3 million blocks)

Height dominating human construction for 4,000 years

Human vision has a finite field of view. Standing at the pyramid's base, you physically cannot see the entire structure without moving. This forces the viewer to mentally reconstruct the whole from partial views, engaging imagination rather than direct perception.

Pyramids as Sublime Objects

Understanding the Sublime as a psychological phenomenon allows us to analyze how pyramids deliberately engineer responses through specific architectural choices. The challenge for pyramid architects was creating forms that reliably trigger Sublime experiences across different viewers and cultural contexts. The solution involved maximizing multiple factors that converge to overwhelm normal perception.

Scale:

Too large to see all at once

Mass that seems impossible (2.3 million blocks)

Height dominating human construction for 4,000 years

Human vision has a finite field of view. Standing at the pyramid's base, you physically cannot see the entire structure without moving. This forces the viewer to mentally reconstruct the whole from partial views, engaging imagination rather than direct perception.

Perfection:

The geometric strategy solves the problem of maintaining impact despite familiarity. Complex forms become comprehensible once you understand their organizing principles, but pure geometric forms like perfect triangles resist this intellectual mastery.

The triangle is simple enough to recognize instantly but perfect enough to feel like an ideal rather than a human-made approximation.

The precision (knife blade cannot fit between blocks) suggests manufacturing tolerances that seem impossible for the stated technological level, creating cognitive dissonance that enhances the Sublime effect.

The simplicity paradoxically makes the achievement more impressive. There are no decorative flourishes to distract from the pure form, forcing viewers to confront the geometric perfection directly.

Perfection:

The geometric strategy solves the problem of maintaining impact despite familiarity. Complex forms become comprehensible once you understand their organizing principles, but pure geometric forms like perfect triangles resist this intellectual mastery.

The triangle is simple enough to recognize instantly but perfect enough to feel like an ideal rather than a human-made approximation.

The precision (knife blade cannot fit between blocks) suggests manufacturing tolerances that seem impossible for the stated technological level, creating cognitive dissonance that enhances the Sublime effect.

The simplicity paradoxically makes the achievement more impressive. There are no decorative flourishes to distract from the pure form, forcing viewers to confront the geometric perfection directly.

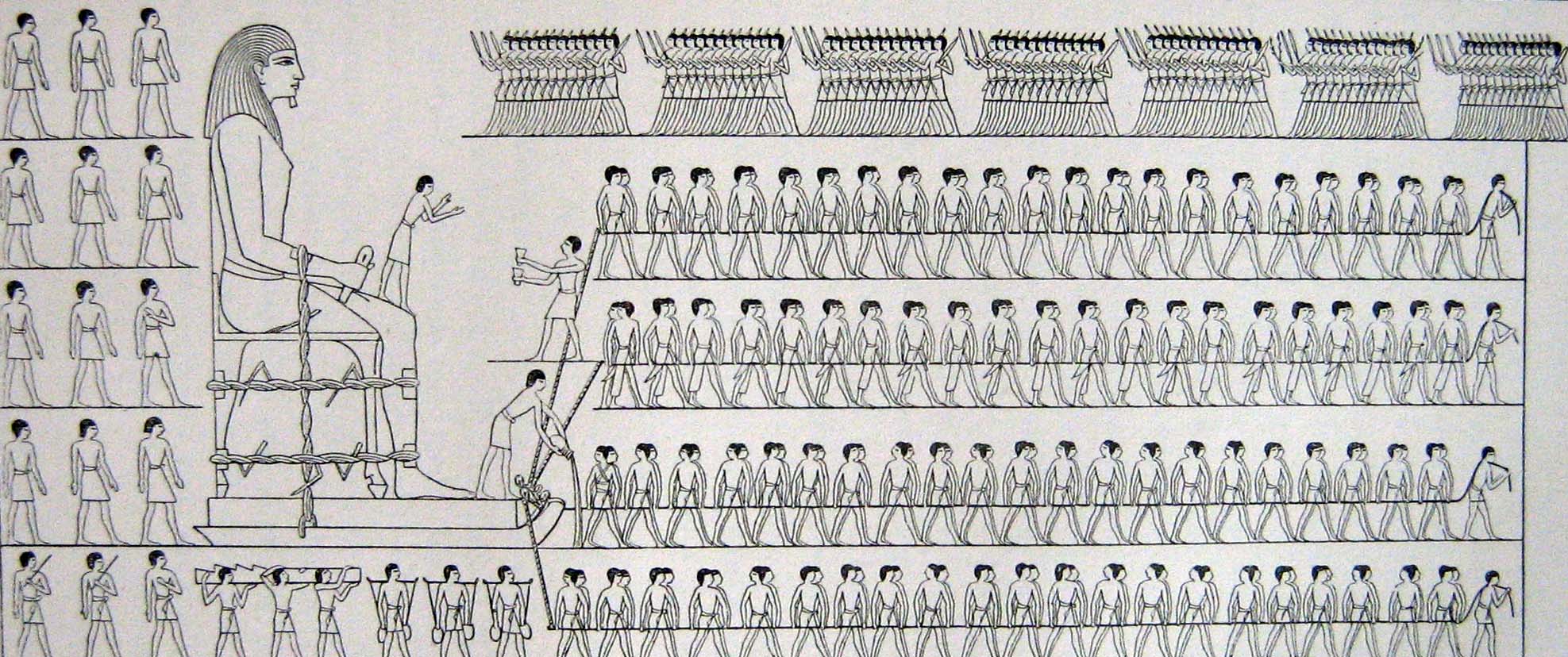

Drawing showing transportation of a colossus. The water poured in the path of the sledge, long dismissed by Egyptologists as ritual, but now confirmed as feasible, served to increase the stiffness of the sand, and likely reduced by 50% the force needed to move the statue.[31]

Drawing showing transportation of a colossus. The water poured in the path of the sledge, long dismissed by Egyptologists as ritual, but now confirmed as feasible, served to increase the stiffness of the sand, and likely reduced by 50% the force needed to move the statue.[31]

Drawing showing transportation of a colossus. The water poured in the path of the sledge, long dismissed by Egyptologists as ritual, but now confirmed as feasible, served to increase the stiffness of the sand, and likely reduced by 50% the force needed to move the statue.[31]

Temporal vastness:

The temporal dimension addresses the problem of creating authority through age. When a structure predates written history and has remained essentially unchanged through the entire span of recorded civilization, it begins to feel like a natural feature of the world rather than a human construction. This temporal scale makes the pyramid feel eternal, suggesting that the power and knowledge behind its construction operate according to principles as fundamental as geological or astronomical forces.

Temporal vastness:

The temporal dimension addresses the problem of creating authority through age. When a structure predates written history and has remained essentially unchanged through the entire span of recorded civilization, it begins to feel like a natural feature of the world rather than a human construction. This temporal scale makes the pyramid feel eternal, suggesting that the power and knowledge behind its construction operate according to principles as fundamental as geological or astronomical forces.

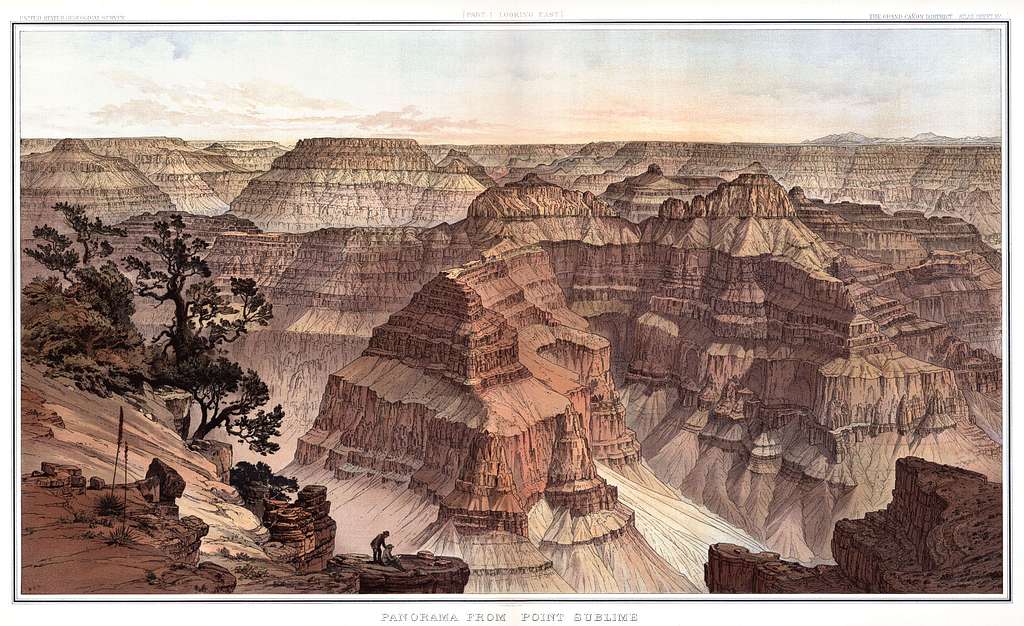

The Grand Canyon evokes the sublime experience through sheer scale and temporal presence. Its vastness exceeds human measure, collapsing distance and time into a single overwhelming view. Image from the Collection of William Henry Holmes - Source

The Grand Canyon evokes the sublime experience through sheer scale and temporal presence. Its vastness exceeds human measure, collapsing distance and time into a single overwhelming view. Image from the Collection of William Henry Holmes - Source

The Grand Canyon evokes the sublime experience through sheer scale and temporal presence. Its vastness exceeds human measure, collapsing distance and time into a single overwhelming view. Image from the Collection of William Henry Holmes - Source

Momentary freezing response:

Brief stillness in posture and breathing

Widened eyes and pupils

Increased attention

Temporary suspension of other cognitive processes

This is the "defense cascade", a mammalian response to perceiving something potentially threatening but not immediately dangerous. It's hypervigilance: body preparing while mind assesses.

Momentary freezing response:

Brief stillness in posture and breathing

Widened eyes and pupils

Increased attention

Temporary suspension of other cognitive processes

This is the "defense cascade", a mammalian response to perceiving something potentially threatening but not immediately dangerous. It's hypervigilance: body preparing while mind assesses.

Physiological Effects of Monumental Architecture

While philosophical frameworks describe the Sublime experience, contemporary neuroscience and psychology face the challenge of measuring these responses objectively and understanding their evolutionary origins.

What specifically happens in human brains and bodies when confronting monumental architecture, and why did these response patterns evolve? Research by Yannick Joye and Siegfried Dewitte shows that when participants viewed images of very tall buildings, they observed:

Physiological Effects of Monumental Architecture

While philosophical frameworks describe the Sublime experience, contemporary neuroscience and psychology face the challenge of measuring these responses objectively and understanding their evolutionary origins.

What specifically happens in human brains and bodies when confronting monumental architecture, and why did these response patterns evolve? Research by Yannick Joye and Siegfried Dewitte shows that when participants viewed images of very tall buildings, they observed:

The freezing response solves an evolutionary problem. When encountering something novel and overwhelming, immediate action (fight or flight) might be inappropriate until better information is gathered? The freeze state allows rapid threat assessment while preparing the body for quick action if needed. With pyramids, the stimulus is too large to represent immediate physical threat (you can't be attacked by a building), but too impressive to ignore as irrelevant. The widened pupils and eyes gather maximum visual information, the attention spike focuses cognitive resources on processing the stimulus, and the suspension of other cognitive processes clears mental bandwidth for assessment. This cascade happens automatically, before conscious thought, making it a powerful tool for architects who understand these triggers.

The freezing response solves an evolutionary problem. When encountering something novel and overwhelming, immediate action (fight or flight) might be inappropriate until better information is gathered? The freeze state allows rapid threat assessment while preparing the body for quick action if needed. With pyramids, the stimulus is too large to represent immediate physical threat (you can't be attacked by a building), but too impressive to ignore as irrelevant. The widened pupils and eyes gather maximum visual information, the attention spike focuses cognitive resources on processing the stimulus, and the suspension of other cognitive processes clears mental bandwidth for assessment. This cascade happens automatically, before conscious thought, making it a powerful tool for architects who understand these triggers.

“Monumental scale triggers physiological and psychological responses: the body freezes, the mind expands. Architecture becomes technology for transcendence.”

“Monumental scale triggers physiological and psychological responses: the body freezes, the mind expands. Architecture becomes technology for transcendence.”

With pyramids, the mind momentarily freezes because the stimulus is too vast to register as an immediate threat yet too impressive to ignore, forcing the brain to pause and categorize the encounter while producing an emotional response that blends fear with fascination.

Buildings triggering this response create memorable experiences. This isn't accidental. It's exactly what architects of sacred and political structures wanted.

With pyramids, the mind momentarily freezes because the stimulus is too vast to register as an immediate threat yet too impressive to ignore, forcing the brain to pause and categorize the encounter while producing an emotional response that blends fear with fascination.

Buildings triggering this response create memorable experiences. This isn't accidental. It's exactly what architects of sacred and political structures wanted.

V. THE SCIENCE OF PERMANENCE

Built to Last Forever

Most human constructions are temporary. Wood rots within decades, steel rusts within centuries, and concrete crumbles after a few generations. Modern buildings are designed with 50-100 year lifespans before requiring major renovation or replacement. The pyramids have stood for 4,500 years with no maintenance, repairs, or modifications, and show no signs of imminent failure. This isn't luck: it's the result of deliberate engineering choices made at every stage of design and construction. The architectural problem becomes: what specific decisions enabled this unprecedented longevity?

Built to Last Forever

Most human constructions are temporary. Wood rots within decades, steel rusts within centuries, and concrete crumbles after a few generations. Modern buildings are designed with 50-100 year lifespans before requiring major renovation or replacement. The pyramids have stood for 4,500 years with no maintenance, repairs, or modifications, and show no signs of imminent failure. This isn't luck: it's the result of deliberate engineering choices made at every stage of design and construction. The architectural problem becomes: what specific decisions enabled this unprecedented longevity?

Built to Last Forever